Ut nihil non iisdem verbis redderetur auditum

- Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis

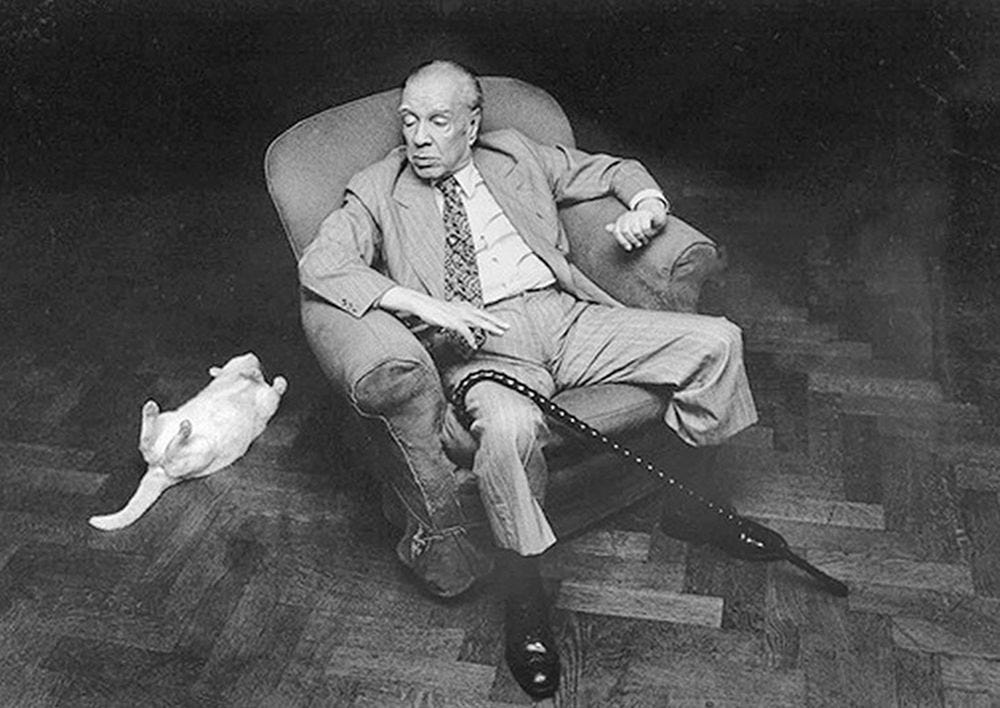

Jorge Luis Borges produced most of his work several decades before much of the world became chronically online. He died in 1986, a few years before the earliest iterations of what evolved into the Internet as we know it were made public. During his lifetime, the idea of humanity being connected in a space that exists seemingly beyond or outside of material reality, a space that contains nearly all human knowledge, was the stuff of science fiction, of kabbalistic dreams (or nightmares).

In fact, flying cars and space travel seemed closer than a digital realm beyond our own (As evidenced by the final scene of Back to the Future which came out a year before Borges died… One can’t help but wonder if he saw it? And what did he think about it?). But the literary prophet that he was, Borges somehow glimpsed the ever-expanding nexus of symbols, data, and imagery in which we’re enmeshed.

Take, for example, his story “The Aleph.” In it, Carlos Argentino Daneri, a pretentious, glory-hound of a poet describes the modern individual, outlining with unnerving accuracy the swamp of data we’ve sunk into. He says that the modern man is “in his study, as though in the watchtower of a great city, surrounded by telephones, telegraphs, phonographs, the latest in radio-telephone and motion-picture and magic-lantern equipment, and glossaries and calendars, and timetables and bulletins”. Due to vast technological advances in our own day, Daneri’s vision of the modern man, derided by Borges’ narrator as, “sweeping and pompous,” has become our banal reality.

With smartphones, computers, and televisions, modern society has slowly become an immense eye, gazing outwards and into the minds of all its members, eternally fascinated with the imagery and information that spirals endlessly within the Internet’s ever-growing labyrinth of networks. Never has a totality of information and imagery been so accessible to the individual human being.

One can, within a matter of seconds, navigate from Wikipedia articles on Plato and Aristotle, to publicly posted photos of family, friends, and strangers, to videos depicting hardcore sex acts. With near instantaneity, the complete human experience is splatted across our screens, ready to be sucked up by our bloodshot eyes. Each one of us has become Daneri’s modern man, sitting in our metaphorical watchtowers, gazing into our smartphones, TVs, and computer screens at something resembling, but distanced from, the real world.

How to deal with this near total access to vast archives of imagery and information and what effect it has on us, has become one of the 21st century’s most pressing questions. Borges, the accidentally literary seer that he was, was ahead of his time, and saw the possibility of the Internet, captured in his themes of labyrinths, networks, reflections, and the endless accumulation of information, and attempted to resolve, or at least to question, how we address such possibilities.

He deals directly with these ideas in stories like “The Library of Babel” and “The Aleph,” portraying different structures which contain a totality of information, while also examining how it’s possible to navigate or escape these totalities in stories like “Funes, His Memory”. Borges wasn’t just trying to write interesting stories; he was deeply committed to using literature as a way to elevate the reader’s consciousness through interactions with frightening paradoxes and scenarios. He wanted us, his readers, to wake up.

The most obvious connection between the Internet and Borges’ short stories is his story “The Library of Babel,” which details a – possibly – infinite library that represents the universe. Mirella Servodidio, in an essay on the connections between the work of Carme Riera and Borges, observes that “Borges’ metaphor for the unfathomable universe [the infinite library], is a clear antecedent of the Internet, that vast and awesome universe of electronic information”. In other words, from our modern viewpoint, Borges’ construction of the Library of Babel, a never-ending network of hexagonal chambers full of books whose contents are mere random permutations seems prescient. The Internet, in its immensity and decentered-ness can be recognized as our own Library of Babel, a space that Mario Vrbančić, borrowing from Foucault, calls a heterotopia because it “undermines unity and turns everything into endless intertextual dispersion”. It is not a stretch, then, to recognize the similarities that exist between Borges’ Library of Babel, with its sprawl of randomly generated tomes, and the Internet.

However, delving further into Borges’ oeuvre, one can find deeper connections between our own relationship to cyberspace and particular stories—namely, “The Aleph” and “Funes, his Memory.” This is important because, for some reason, little academic work has been done on the connections between Borges’ fiction works and the Internet. Part of what I want to achieve is to illustrate how deeply connected the themes over which Borges obsesses are–mirrors, labyrinths, memory, and forgetfulness–to ways in which we experience the Internet and its vast digital spaces. However, I can make these connections, it’s important to review some of the critical work that has been done on Borges’ story “The Aleph,” and how this work gestures towards my own arguments.

Many different theoretical frameworks have been applied to Borges’ stories. “The Aleph” one of Borges’ more famous fictions, is told by a narrator, named “Borges,” who finds out that a cousin, Carlos Argento Daneri, of a former love, Beatriz Viterbo, keeps in his cellar a tiny point of light through which one, if positioned correctly, can witness the entire universe, completely and instantaneously. Due to its complexity, and ambiguity, this story has been subject to numerous interpretations, three of which concern this essay.

The first of these are the literary analyses of “The Aleph,” summed up nicely by Humberto Núñez-Faraco in his article, “In Search of the Aleph: Memory, Truth, and Falsehood in Borges’s Poetics”. Núñez-Faraco takes a somewhat biographical perspective in his interpretation, observing that many moments in the story align with Borges’ love for an acquaintance which Núñez-Faraco maps onto a comparison between themes in “The Aleph” and themes from Dante’s Divine Comedy. Núñez-Faraco’s analysis is important because it establishes relationships between the narrator “Borges,” the Aleph itself, and Daneri and Viterbo, positing that the Aleph is a device for seeing the truth, like Dante’s visit to paradise. Thus, the Aleph becomes a way of deciphering reality, of literally breaking down it’s complexity into instantaneous overlay of everything, all at once.

There are two conflicting points of view which both disagree with Núñez-Faraco: those of Jonathan Stuart Boulter and Mario Vrbančić. Boulter and Vrbančić both examine “The Aleph” from a postmodern perspective, dissecting the story with the help of Baudrillard, Foucault, and Jameson. Vrbančić sees “The Aleph” as an exploration of Foucault’s theory of heterotopia, depicting a totality contained within the Aleph as a space which collapses all boundaries and de-centers the entire universe.

Although interesting, this analysis does not take into account the postscript that makes up the final section of “The Aleph” in which “Borges” declares that the Aleph in Daneri’s cellar was a false Aleph and that the true Aleph, if there is one, is invisible. In contrast, Boulter uses this postscript as a way to examine Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra, showing how the Aleph is a nearly perfect representation of the fourth phase of the image, in that, according to Baudrillard, “it bears no relation to any reality whatever: it is its own pure simulacrum.” In my next essay, I will build on Boulter’s work to illustrate the Aleph as a simulacrum and push it even further. The Aleph isn’t merely a simulacrum but a hyperreal version of reality, which, bit by bit, overlays our actual reality, becoming the map that replaces its topographical source.

Thanks for writing this. I gave up on thinking seriously about the internet a while ago, but if there's Borges to entice me I might try to do so again via your essay.

You may already be aware of this, but as a fellow Utahn I have to put it out there: Borges actually visited the BYU campus in Provo towards the end of his life. There's an interview about it here: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol34/iss1/5/

> "...modern society has slowly become an immense eye, gazing outwards and into the minds of all its members, eternally fascinated with the imagery and information that spirals endlessly within the Internet’s ever-growing **labyrinth** of networks..."

*"Hello? You rang?! 'We Have Always Lived in the Maze'!? I'll be right there..."*

(lol good job here bro. love me some borges!)