The vastness of the Internet, along with its ever-growing complexity and depth, raises questions about the very nature of perception and presence; about the divide between real and symbolic. Despite it’s apparent depth and wealth of information—the seemingly endless waves of meaning—the Internet, and the data it spews, is presented to us on flat screens, robbed of the dimensionality that we typically ascribe to and perceive as reality. That observation appears banal at first glance, but, as McLuhan said, “the medium is the message,” and although he didn’t intend it so literally, the dance of pixels across glass and indium tin oxide has become the portal through which we experience reality. The small surface upon which our eyes spend hours skating has mapped itself over the world and is slowly alienating us from that old domain of authentic sensory data.

It’s not unlike the Aleph. In Borges’ story, the Aleph is a small point of light through which the narrator can view everything in the universe, from every perspective. The narrator, while looking into the Aleph, sees “millions of delightful and horrible acts… that all occupied the same point, without superposition and without transparency.” What he saw, he says, was “simultaneous” but due to the nature of language, he can only write what he sees successively. At this point, Borges’ narrator fills an entire page of things that he witnessed, repeating over and over the phrase “I saw.” “The Aleph” becomes, for Jonathan Boulter, “an exploration of the possibility of collapsing time/space into its own simulation to make it intelligible at the level of the human.”

I’s say that this definition of the Aleph is one that can be equally applied to the Internet, although the Internet has not yet reached the sort of hyperreal totality represented by the Aleph (although maybe one day we’ll be staring into our own personal Aleph’s using our Vision Pros). However, the Internet, as it increases in size, encompassing more of human experience and time and then reducing it to information that is accessed through screens, resembles closely the experience of looking into the Aleph. If it were compared to a text, it would not be the sort of “writerly” texts which Barthes describes in his seminal text S/Z, but would, in fact, invert what Barthes calls a “galaxy of signifiers” to become a signified containing a galaxy, a (literally) single point of entrance that, due to its totality, is unbending and uninterpretable.

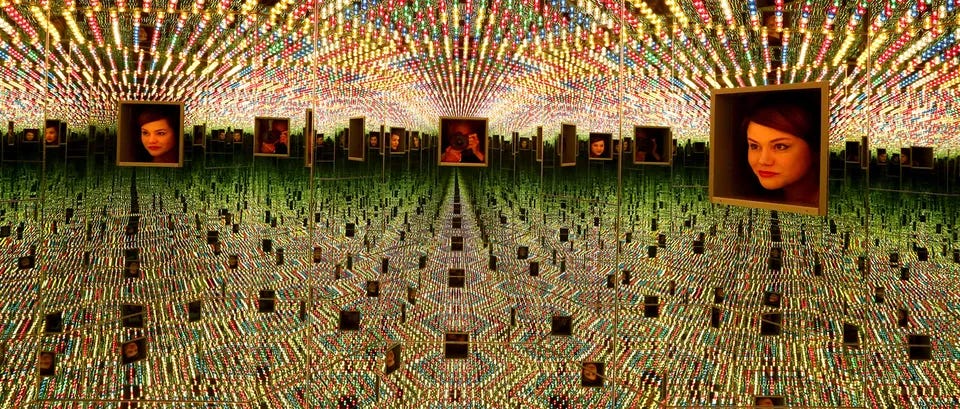

On the surface, the endless flow of the data offered by the Internet mirrors the human concept of infinity or eternity. The proliferation of links, allowing one to move seamlessly amongst the archives of our civilization, gives Internet users (all of us) the impression that they exist above or outside the flow of information. We perceive ourselves as privileged viewers of humanity’s accomplishments. Similarly, while gazing into infinity, the narrator ‘Borges’ sees, among other things, “endless eyes, all very close, studying themselves in me as though in a mirror, [and] saw all the mirrors on the planet.” In addition, everything he sees is repeated infinitely, with only tiny variations because he saw each of them “from every point in the cosmos.”

That is to say, the Aleph is a machine which produces, like a television or a computer screen, endless images and then infinitely replicates them, providing a never ending stream of reproductions and perspectives. Completely disconnected from any reality, this endless totality of images becomes a supreme simulacrum which disorients the viewer and, as Boulter explains, in presenting everything at once, without context, “stands as an emblem of history’s denial: as it presents time and space simultaneously, the telos aspect of history (history as narrative, history as progression from one time to another) is denied.” This same denial of history is present in our interactions with the Internet, specifically in how we utilize social media. Message boards, comment sections, and social media pages become places in which images, sounds, words, and experiences are endlessly mixed and blended, with little or no regard to their place within a historical context. More specifically, the idea of the meme, an image or phrase severed from its original context which is endowed with new or symbolic meaning as it passes from one user to the next on social media, is the perfect example of how the Internet resembles the Aleph in its ability to replicate without regard to context anything in existence.

What so frightens “Borges,” and what should give us pause, is his emphasis on the endlessly repeating eyes and mirrors—all observing and reflecting, constantly and simultaneously. Borges emphasizes the voyeuristic nature of the Aleph, which forces the viewer to gaze and be gazed upon, infinitely and all at once. The Aleph, like the Internet, is a machine that produces reflections and copies, infinitely spitting out simulacra which distance the viewer further and further from the reality that they supposedly represent.

The ease with which we now record ourselves and our surroundings has marked a new era in human existence, one in which reflections or copies vastly outnumber their originals. Such a shift in the human experience was not lost on Borges who, in his other works and poetry, expresses repeatedly a fear of mirrors and reflections. For instance in his poem, “Mirrors,” the poet describes how he looks on “them as infinite, elemental / fulfillers of a very ancient pact to multiply the world, as in the act of generation… / they extenuate this vain and dubious world / within the web of their own vertigo” and, in them, “everything happens and nothing is remembered.” This poetic description of mirrors can be applied neatly to the Aleph. Nearly every facet of human experience, from the innocent to the obscene, is captured in the Aleph and as Boulter indicates, borrowing from Fredric Jameson, it becomes “’obscene’ or ‘pornographic’ knowledge, insofar as it reveals en abyme the total workings of the world.”

Again, it’s easy plug Boulter’s description of the Aleph into a comparison with the Internet: through social media, photos of ourselves are shared and commented on over and over again, multiplying as they’re posted and re-posted. We lose control of them and they no longer represent us, becoming instead shadowy simulacra moving in endless circles through a non-material, digital world. One must only consider the vast amounts of violent and pornographic material, severed from any context and reduced to single images, which circulate on the Internet and are viewed with extreme regularity to understand how far removed from reality the most powerful and traumatic human experiences can become when viewed on the Internet, and social media in particular (or in the Aleph).

Society’s immersion in the wealth of simulacra that the Internet offers has meant a general loss of the ability to recognize the difference between an image and a copy of an image. A consequence of this loss is a dulling of artistic sensibility. The user of the Aleph is the character Carlos Argentino Daneri, the cousin of Beatriz Viterbo, a woman whom “Borges” once loved and whose repeated visits to her house become a simulacrum of sorts, repeated each year on the anniversary of her death but, each year, with less relation to his love for her. Daneri – whose name it has been pointed out by various scholars is constructed from parts of the names of other poets: [Dan]te Alighi[eri], Pablo [Ne]ru[da], and Ruben [Da]rio (Núñez-Faraco) – uses the Aleph as a means to look out at the world and write a poem, called “La Tierra,” which encompasses the entire earth. Tiresome and overwrought, the poems that Daneri reads to “Borges” are commented on by the narrator as having “nothing memorable about them” and that “application, resignation, and chance had conspired in their composition.” In his poetry, Daneri uses multitudes of historical and literary references, allusions, and multiple languages in an attempt to poetically contain the world. His work is a mirror, a poor one, of what the Aleph does which is to contain the entire universe in a single point.

However, what is plain after reading Daneri’s poetry is that, due to his use of the Aleph, he is unable to look beyond the image produced by the Aleph—which is merely a copy—and actually “see” the world he is attempting to describe. His poetry becomes endless descriptions of images for which Daneri has no context or experience, of places like “the sheepfold that suggests an ossuary” in Australia, which he believes to be full of “formal perfection..., scientific rigor… [and] severe truthfulness.” Daneri, in his attempts at cataloguing the earth, manages only to capture the form of things while ignoring, or perhaps unable to see, the context surrounding them that endows them with meaning. He is a mere collector, as Baudrillard notes in Simulations, seeking to “immortalize everything by reconstitution,” the act of which is a mere reflection of what the Aleph does (which is to reflect). Daneri, in his pomposity, pretensions, and, ultimately, his success (his book of poems wins second place in a prestigious literary contest in Buenos Aires), can be seen as an analog for the modern Internet user. He is the person who feels that his access to a totality of information has granted him a place above and beyond humanity and history. Because he “sees” everything, he thinks that he knows everything and he conflates a totality of imagery and information for a totality of knowledge. What’s so frightening about this illusion of knowledge is that it doesn’t only deceive Daneri but also deceives the Buenos Aires literary establishment, which can be interpreted as Borges saying that those who examine and judge knowledge are losing the ability to do so because of the proliferation of simulations and copies.